Anne Desmet, one of this year’s Prize Exhibition judges is one of only three engravers to ever be elected as an Royal Academician.

As a wood engraver, Anne describes her work as ‘creation in light’. In this interview, she explains her techiques, her inspirations and her passion as she compares her cutting blades to a calligraphy pen with a myriad of nibs – capable of creating a huge range of expressive marks.

What was your earliest memory of making prints?

I made a very bad linocut of a squirrel in a tree when I was about 12 or 13, at school. But my school (a comprehensive school in Crosby, Liverpool) had rather poor quality equipment –

blunt tools, old stiff lino, poor quality paper – so the resulting print was pretty terrible and I

wasn’t inspired to make any more. In, fact I forgot all about printmaking until I went to art

school (Ruskin School of Art, Oxford University) in 1983 to take a Fine Art Degree. I was

introduced to etching, woodcutting, wood engraving, copper engraving, screenprinting and

stone lithography there, all within a fairly short space of time. I enjoyed all of them (except

screenprinting) but wood engraving and stone lithography were the techniques that particularly captivated me and continue to do so.

What inspires you?

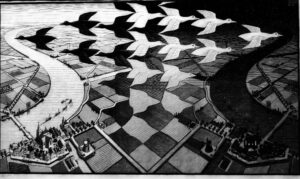

Many things! As a teenager, I was hugely inspired by the Latin writer Ovid’s ‘Metamorphoses’. These are Roman retellings of Greek myths featuring stories of transformation of one sort or another: Daphne is changed to a tree, Arachne to a spider and so on. I was, at the same time, very much inspired by the metamorphosing images of the Dutch artist M C Escher so my early drawings and prints at art school had strong themes of metamorphosis and transformation.

At art school too I was inspired by drawing the life model and by making portrait drawings of my friends, many of which resulted in images of metamorphosis. Some years later (1989-90) I took up a Rome Scholarship in Printmaking which gave me a year living and working as an artist in Rome. There I became hugely inspired by the ancient, medieval, baroque and even the contemporary architecture of Rome – all of which coexists in a fascinating jumble. It seemed to me to speak of the coexistence of millennia of human history and to hint at the huge cultural changes and the weight of history about the city. That seemed to me like a living metamorphosis of a sort and has inspired my work ever since.

There was also something incredibly special about the dramatic light and theatricality of Rome which I found inspiring. I have lived in London for the past 30 years (with regular trips back to Italy) so the architecture of London and other cities also now inspires me. Another strong source of inspiration is the idea of the biblical Tower of Babel. I have made many invented tower images recalling the Flemish painter Bruegel’s historic paintings and also reflecting historic towers in Italy and more recent city skyscrapers. I think towers have a lot to say about human aspiration, ambition, humour and folly. They are endlessly fascinating subjects.

What is the greatest highlight of your career so far?

That’s a really difficult question! The greatest thrill I felt was, I think, way back in 1987, right

at the very start of my career when I won a prize for a stone lithograph print I entered for a

competition at the Royal Festival Hall. I was only 23 at the time. I have no artists in my family and had no real idea of whether a career as an artist was even possible, so I was very much ‘testing the waters’ of trying to make ends meet as an artist back then. That prize gave me a real thrill because it was the first ‘proof’ to me that I could really do this! Two years on from that I gained my Rome Scholarship which was an incredible experience which continues to be hugely influential in my work. And much more recently, my election as a Royal Academician – I am only the third ever artist elected to the Academy on the strength of their wood engravings – has been a great honour and has made a marked difference to the success of my career.

If you could have produce one piece of art from the past what would it be and why?

I would like to have created Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Great Tower of Babel, an oil painting

on wood panel (painted in 1563) now in the Kunsthistoriches Museum in Vienna. I have not

yet actually seen the original of this painting but have studied reproductions of it in many

books over many years and it has inspired many of my own tower engravings. There is a

fantastic combination of drama, detail, light and shade, realism, surrealism, invention and

fantasy about it. The combination is entirely intoxicating and utterly memorable and beguiling. An added factor for me is that Bruegel, a Flemish Renaissance painter, sets his Babel amid the historic Netherlandish city of Antwerp (now in Belgium). My father was a Belgian and I have cousins, to this day, in Antwerp, so this gives this painting an added resonance for me.

You are currently the only Royal Academician elected for their work as an engraver, what is it you love so much about the medium?

As a wood engraver, the images one engraves on pieces of end-grain boxwood (and various

other very slow-growing trees) are creations in light: one engraves all the light parts of the

image (a bit like making a drawing in white chalk on black paper) and it is the uncut parts of

a block which carry the printing ink and provide the printed parts of the image. The engraved parts remain the colour of the printing paper in the finished works. But the effect of this is that one is ‘engraving in light’ and so one’s work can have a strong sense of theatricality and drama about it, which has a strong parallel in the strong, dramatic sunlight and deep shadows of Rome. I love that idea of ‘engraving in light’ and the particular qualities of light that that brings to the finished prints.

I also love the crisp graphic clarity of the medium and the sense of working on an organic substance. I am particularly inspired by the irregular shapes of the blocks, especially roundel-sections; their diverse shapes can inspire ideas for compositions that one wouldn’t get from a rectangular canvas or blank sheet of paper. The tools of the engraver’s trade are also wonderful and diverse: a wide range of fine steel blades set in beautiful mushroom-shaped wood handles. Each cutting tip makes a subtly unique mark – so one can create effects much like having a calligraphy pen with a vast range of nibs. Yet the engraving tools facilitate the creation of marks with rounded edges or square, angular cuts, fine sweeping curves or geometric angles – a far greater variety of mark than I believe any combination of pens can accomplish – and that is

entirely inspiring to me!

What are you currently working on?

I have just finished a large engraving – commissioned by Manchester Metropolitan

University’s Special Collections Library. The theme was to create an image that related

somehow to wood engraving and its history over the last couple of hundred years. I made

an engraving based on a model of still-life objects I assembled in my studio. All the objects

were chosen for their relevance to some aspect of the history of wood engraving and/or to

my own personal history. The assemblage took on the form of a tower somewhat reminiscent of that of Bruegel. I was definitely inspired by this commission and think it may possibly change the direction of my work going forward. I am contemplating the result at the moment (I only printed the block a few days ago) and am now working on ideas of what I might want to engrave next!

You have participated and been shortlisted for the New Light Prize in the past , what were you favourite memories of the experience, and what advice would you give to this years participants?

My favourite memory of the New Light Prize in the past was of going to the Bowes Museum

in Barnard Castle for its opening. I had never visited that museum before and it’s a wonderful place – especially its extraordinary silver swan automaton (c.1773) which is an artwork of mind boggling ingenuity and sheer beauty and is alone well worth the visit!

I find it hard to give advice to other artists except to say that it seems to me important to follow your heart and your gut instincts when trying to make art. If you believe in your own work and feel it is somehow ‘true’ to your own intentions and is the best work your mind and hands can make, then that is likely to be apparent to the viewer and to leave a strong impression on them too. I am sure the maker of the swan automaton must have felt those same feelings nearly 250 years ago!