A London-based arts writer and editor, Sam Phillips is one of this year’s New Light Prize Exhibition judges.

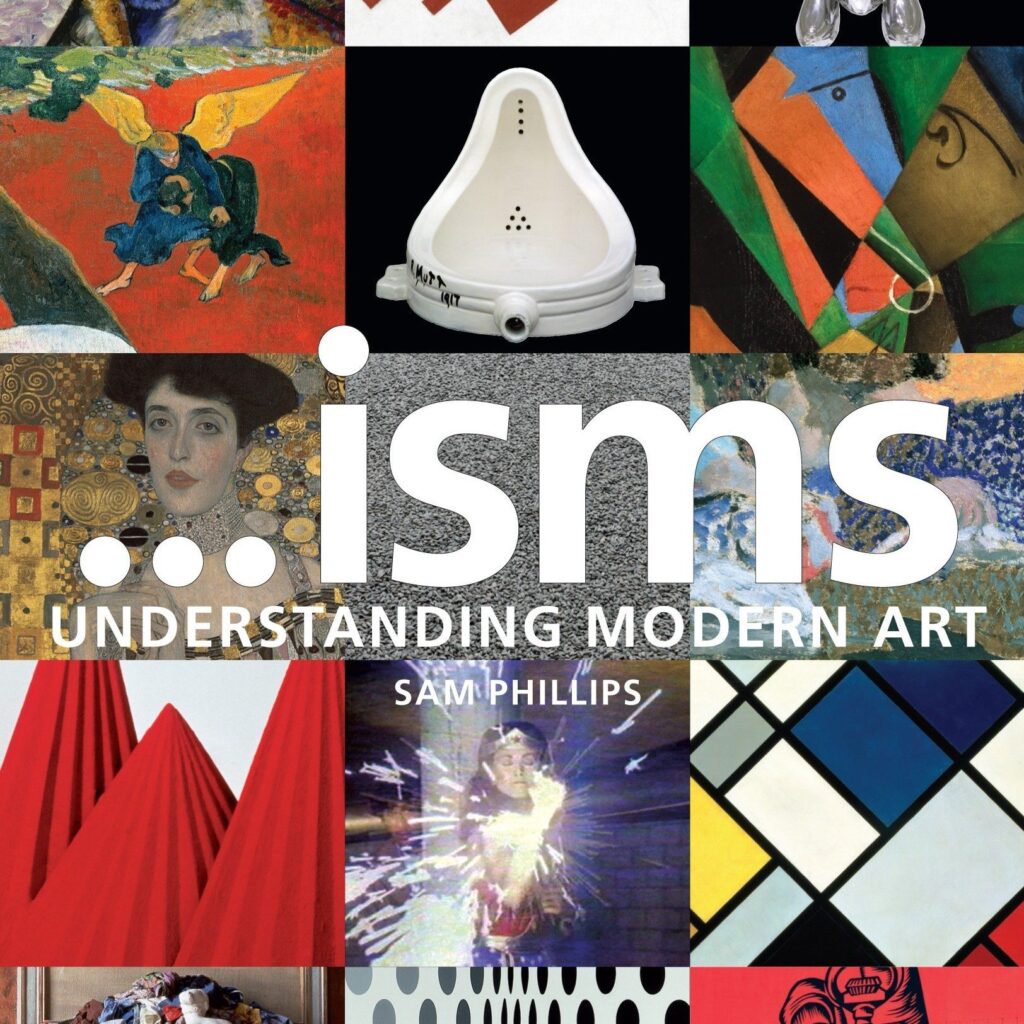

Sam is the author of a guide to the capital’s art collections, The Art Guide: London (Thames & Hudson, 2011), and Isms: Understanding Modern Art (Bloomsbury, 2012), an introduction to avant-garde art movements.

He has contributed articles on art, design, architecture and music to a wide range of a publications, including The World of Interiors, Time Out, I-D, Artists & Illustrators, Blueprint, Asian Art Newspaper and The Independent. He has edited art books, catalogues and journals for galleries and publishers and managed print and publications for the Serpentine Gallery.

New Light asks him some questions:

You’ve recently become a father, congratulations! If you were to introduce your

daughter to five artists’ work, what would you choose?

Thank you! And what a great, if difficult, question. At this tender age, I would probably

introduce her to Yayoi Kusama, the nonagenarian Japanese artist who covers paintings,

sculptures, all types of other objects and entire rooms with colourful dot-based

patterns. I imagine my little girl would go gaga over them. But when she gets a bit

older… I would probably say Artemisia, Poussin, Picasso and Van Gogh, which are four

artists I’ve been looking at a lot this week. I could probably pick another four next week.

You will have met many artists in your career. Do you think there is such a thing as

a ‘great’ artist, and is it possible to know who will be considered as such in the

future?

Yes, there is such a thing as a ‘great artist’, if by that you mean someone who really

stands out as outstanding from their time. All taste – and opinions about who is great

and who is not – is ultimately culturally and temporarily specific, as well as personally

subjective. But that subjectivity does not mean we should ditch the term ‘greatness’:

there can be very persuasive reasons to define someone as great.

When I started writing about art in the 1990s, there were contemporary artists

who were celebrated that are passe now. It is hard to say whether they will come back

into fashion again. In a few decades time, with the distillation that time allows, their

aesethetic and connection to the story of 1990s art (culture cache and context) may

fascinate and intrigue people. Certainly, artists who have an original, singular,

immediately recognisable visual language have, traditionally, fared well over time.

Modigliani is a case in point: actually I think his work is pretty inert and boring, but his

the style of his figures (although nicked from Cycladic art many centuries earlier) is so

recognisable. The fact that he lived hard and died young helped, connected every

elongated nose to his dramatic life story.

If you could interview any artist dead or alive, who would it be and why?

Mondrian, if I could time-travel to the time he started moving to abstraction. Or Philip

Guston, when he started painting figuratively later in life. I think that conversion to a

completely different mode of work is really fascinating.

The famous art writer, Herbert Read, was born in North Yorkshire – not far from where

New Light was founded. In the age of the internet and Instagram, what do think is

the role of the art writer?

Writing about art – if the writing is lucid and interesting – can definitely change the way

one views the art. It gives a way-in, or multiple ways-in, allowing the reader to see the

artwork freshly or differently. The reader might not share the writer’s perspective, but

it opens up thoughts on how something appears and the context in which it was made. I

don’t see the internet or Instagram changing that, although online art writing is often

shorter, to deal with the immediate gratification that the internet encourages.

Both your books ‘Isms’ and ‘The Art Guide: London’ provide insightful, accessible

and functional approach to enjoying art. Tell us your secret – what’s that trick to

writing about art in a way that explains its complexity without becoming

inaccessible?

Description. People rush to theorising or judgement when they write about art, as they

think that is the way to seem like ‘a proper critic’. But description is everything in terms of communicating what art is accessibly; and through one’s choice of description one is

also, of course, judging. Also my second tip on this front is: assume no prior knowledge.

What benefit do you think the arts have in society? Do you think that the current focus

on art’s social function, ie, the well-being benefits of art will have an effect on how artists

work? Should it?

The arts, in their widest sense, are beloved by everyone – whether it is music listened to

by teenagers, interior design of hotels, film, blockbuster art shows etc. Life would be

pretty bad without the possibility to enjoy such things. Life would continue, with

personal artistic expression continuing, but the public and private realm’s support of

culture clearly is a virtuous circle in terms of well-being and mental health. Most artists

would support this idea. But artists should not feel they have to amplify the social

function of their work, in the way it is made or distributed or consumed. Artists can do

what they want (laws permitting).

What do think is the value of arts prizes?

I know the idea of competition in art has become frowned upon a bit; illustrated by the

recent decision to award the last Turner Prize to all nominees. Personally I think art has

always been very competitive, as well as very collegiate, field, and that has often been

productive in spurring artists on. It is artists (rather than critics) who in my experience

are often most acerbic about other artists’ works. They enjoy the grit of criticism.

Taking the subjectivity I discuss above as a caveat, I think prizes do incentivise artists to make work, encourage successes and expose works to a wider audience, as

well as making art lovers visit galleries and look harder.